Believing in the Revolution of Everyday Life with Wan Ing Que and Marika Vandekraats

Commissioned by TENT Rotterdam, 2024

Starting from thinking of the role of anthropology and activism within art, Marika Vandekraats interviews Wan Ing Que on her practice of story-telling. Using food, writing, and theatre, Que holds the voices of many in her practice, shifting from organising, to teaching, to hosting. Be it on a plate or shadow puppets marching through the streets of Utrecht, the two talk about how Que’s practice has been shaped through the many friends and feminist figures in her life.

Marika: Hello Wan Ing!

We’ve known each other now for about 3 years, meeting first when you were my tutor at Dutch Art Institute, and now knowing each other as friends. I wanted to speak to you about your practice because I’m constantly inspired by the ways you transform institutional spaces into spaces for holding and hosting, where questioning can take place and collectivity formed. I know your practice did not start from art per se, but rather from anthropology. Can you tell me what was your focus in anthropology and how that brought you to work with art institutions?

Wan Ing: Hi Marika! It’s been a good 3 years of mutual inspiration! Thanks again for this invitation.

You’re right, I didn’t train in art but in anthropology. I wanted to change the world and work for Oxfam Novib. As my studies progressed, I became critical of developmental aid and turned to anarchism instead. During my bachelor research in the Danish anarchist commune, Christiania, I got interested in self organisation, collectivity and the decolonization of daily life. For my masters, I joined the Occupy movement in New York City focusing on storytelling, militant ethnography and possible roles of a radical intellectual within social movements. [1]

In the end, it was my activism that got me into art. Although almost graduating at the time, I joined a student collective called Kritische Studenten Utrecht that had its base in de Rooie Rat, the local anarchist bookshop. We organised info events and reading groups, ran campaigns, joined demonstrations and put out a newspaper. At some point we got an invitation from a local art institution called Casco to work on a project about the commons and alternative economies. From there, Casco’s director at the time, Binna Choi, took me under her wing. Supposedly that was because of the cheesecake I brought to our first meeting, but really she wanted an activist on her team. The work Casco did was political and collective, nothing like what I thought art was. I found that my anthropological training was useful.

Those first few years at Casco, while still participating in activism as part of a queer feminist and anti-racist movement, were foundational for my becoming a community organiser. It also shaped my cultural work within art, education and social movements. The action-research I started doing then solidified my current practice in other institutional and non-institutional spaces.

M: It sounds like you have spent a lot of time being embedded in communities that were engaged with your research. I think this way of working is crucial to a lot of cultural spaces in this day and age because of a desire to share the stories of many voices, but also perhaps to combat the idea that art institutions can feel like exclusive spaces. I know for myself when first entering into the art world through my studies, the so-called white cube felt inhospitable and elitist. Perhaps this was a similar feeling for you before you began work with Casco. I am curious about how it was for you to work at Casco, and what kind of tools that you picked up from your anthropological background helped you when working within the institution?

W: I relate to the feeling of the white cube feeling elitist. Inhospitable, well, for my work, the white cube is definitely something that totally scares me. My mind just goes blank, it doesn’t inspire me. However, it depends what’s the work, right? I did grow up with it: my uncle is an artist that works within white cubes. I remember loving wandering around in his installations and trying to solve his puzzles, grasp what he was showing us, how his mind worked. I think there are many art worlds. Art is part of culture too, and culture is made and kept alive by people. It’s a pity that in the high-brow art world, where the big business is, art is for rich people to consume and to gain status. Objects and money in those art worlds become more important than people, community or the environment. Those art worlds and the institutions that serve it were historically set up to be exclusive and in practice, are violent too. So I’m glad to see a growing intention to make art institutions more polyvocal.

When I started working at Casco I remember being very confused in the beginning, because indeed I thought most art was about paintings and sculptures. I didn’t know that art institutions could be socially engaged or interested in community building, I thought those things happened at cultural centres, book shops or music venues. At Casco I was exposed to amazing curatorial and artistic practice and research where the work was geared towards prefiguring non-capitalist ways of being. People experimented with alternative economies and invited artists who were working to support homeless and undocumented people or those who organised against the squatting ban. It was difficult to grasp and explain to the outside, but it was collective and engaged with radical politics. I had no idea art could be that.

My anthropological perspective, that was fieldwork based, focused on stories and the political, was welcomed. It complemented theory predominantly coming from art, postcolonial feminism and philosophy. My research practice had trained me in attuning to the space I found myself and to the people in it. Due to my research interests, I was especially attuned to people meeting or coming together to do collective work towards social change. In that sense my listening and note taking skills turned out helpful for needs during collective research or in times of production. Also I was encouraged to grow and develop my budding experience in horizontal and consensus based facilitation processes. Meanwhile I was fed new critical theory and perspectives, and asked to both put things into practice as well as write about it. I loved that, because in university, ideas would stay on a theory level with the option for visual support.Then mostly the outcomes were text and complex academic language. In Casco, I saw how art could allow for wild experiments in how to apply theory to the real world and how lessons from such experiments could be shared in different ways.

M: So true, I remember when we met while I was in my studies, you introduced many different tactics of learning and listening with one another. A personal favourite of mine was the “Haunted Bookshelf” workshop you organised where we would repeat and memorise lines or paragraphs from writers we found inspiring. By using the same methods of traditional schooling, we instead learned to remember words that could inspire us, rather than the usual facts we are taught to remember in traditional school environments, facts that most often centre the western, colonial narratives of history. Now I am glad to say I can conjure up Dionne Brand’s poetry at any moment.

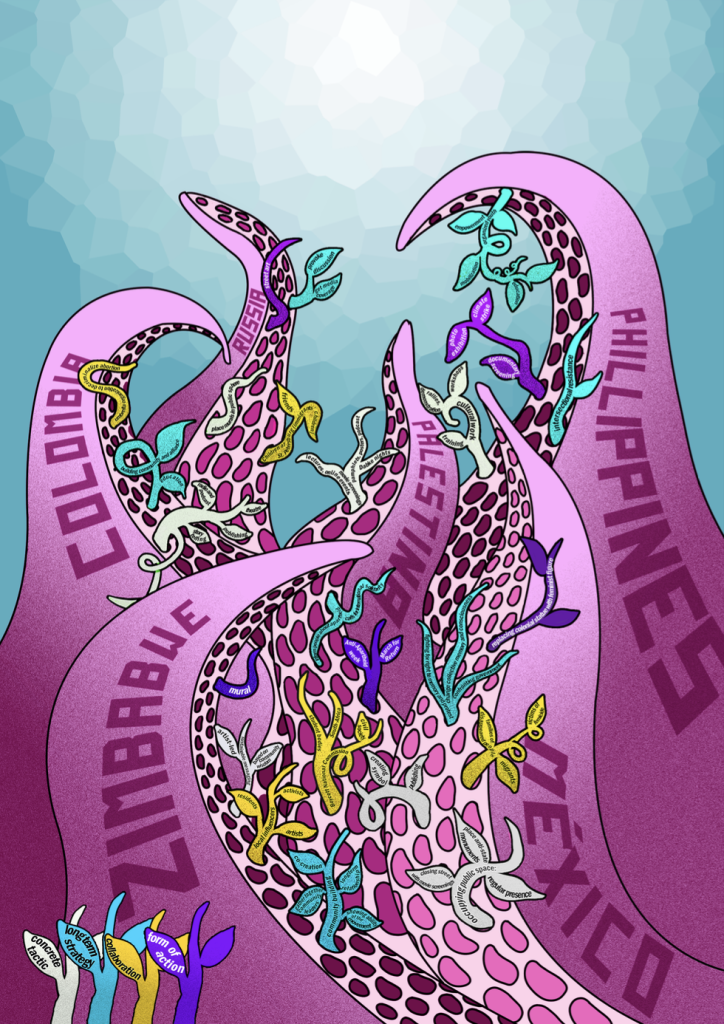

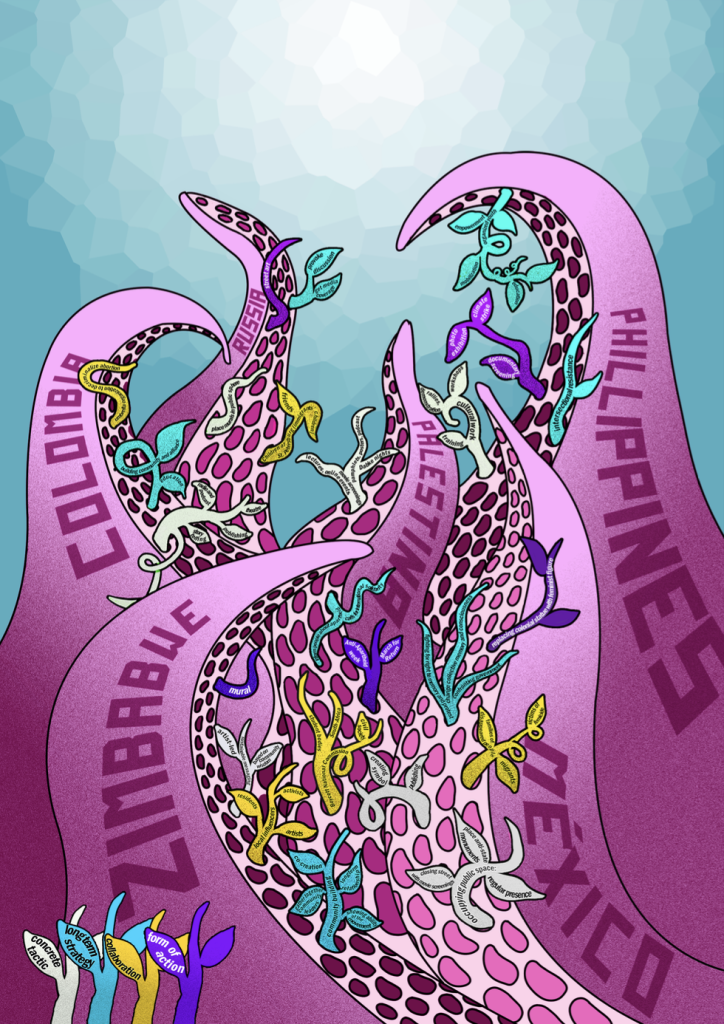

You also introduced a method called harvesting, which you utilise in your recent report made for Stichting DOEN and Actiefonds, “The Other-Monsters”. How I remember you framing harvesting is as a form of collective note-taking that helps the group working together to give notice to the memories, thoughts, and experiences shared around a topic. Please correct me if I’m mis-representing the method! “The Other Monsters” is a really insightful research paper that explores and shares modes of radical imagination used by activist movements throughout the world, organisers all around the world, from Mexico, Columbia, Palestine. I think your way of sharing the harvest method through the visual language of the tentacular arms has a really unifying feeling to it, as if all these methods used by all these movements share the same body. Perhaps a sentiment that can be shared by activists globally that the fights for justice are all connected. Can you elaborate on what inspired you to explore radical imagination?

W: It’s nice to read how you understood harvesting. Yes, it’s like that, a way of taking notes during meetings or of conversations, both in text and visually, sometimes accompanied with drawings if there is time to spend afterwards. I think that the term “harvesting” took root during Documenta 15, where it was and still is a regular practice for the lumbung community. This in turn came from Ruang Grupa’s experience as a member of Arts Collaboratory (AC), a network of 24 arts organisations, mainly in the global south, except for stichting DOEN, who was the core funder until 2021 and Casco, who acted as facilitator in AC’s transition towards a self-organised network. I’m not entirely sure, but I think it is a term they were introduced to when they explored facilitation methods with “the Art of Hosting”. For me personally, harvesting is a beautiful word for what is also called taking minutes or notes, mind-mapping and diagramming. Or a way to remember what was said during a gathering for further study and/or report back.

The illustration you shared is part of a report on radical imagination within social movements. It was done by amazing artist and compa diana cantarey.[2] The report itself was commissioned by activist fund Actiefonds, who in turn were asked for the research by Stichting DOEN from whom they had received funding for “artistic direct action”. They asked me to do interviews with activists whose organisations or actions had received support from Actiefonds and write on how their radical imagination fueled social change. They were specifically interested in these four categories listed in the corner: forms of action, strategies, tactics, and collaboration. I distilled those things from the interviews I had and diana took it from there. Her visualisation to me is also a form of radical imagination that in turn inspired me to elaborate on the place of monsters and tentacled beings in the context of resistance.

Radical imagination as a concept has been extensively written about in social movement research since 1968, when social movements all over the world adopted the Parisian slogan “power to the imagination”. I followed many other writers and organisers in emphasising the importance of imagination in order for us to imagine and experiment with the ways out of capitalist society. I wrote on the radical imagination first in my master thesis on Occupy Wall Street. The stories I told there illustrated their enactments of it through horizontality and community building and also the problems that I felt impeded that imagination: capitalism, police violence, and internal conflict resulting from existing power dynamics and oppressive systems that were naturally reproduced. I remember Cornell West saying at the New Left Forum about how even though Occupy was marvellous, just gathering together on a square wasn’t going to solve 500 years of systematic oppression.

In the report for Actiefonds, I draw on social movement theory, feminist sci-fi writers and Lola Olufemi’s writing of the otherwise to think through radical imagination.[3] I argue that any act of resistance that confronts the status quo, and makes possible what was considered impossible before, can be considered as the radical imagination. The work of the artists and activists I interviewed, in all their diversity of tactics and strategies, did exactly that. Their actions are in service of people and justice or building solidarity and community and are as such, in whatever form, both manifestations of radical imagination and fueled by it. In these times of neocolonial onslaught, climate collapse and rising fascism, we are in dire need of other kinds of imaginaries that can lead us out of the ruins of capitalism, patriarchy and colonialism.

M: Interesting this connection between tentacular beings and monsters as a visualisation of radical resistance. I have to think of Donna Haraway’s proposal from the Chthulucene, a term she uses to describe the many ways that we (we being us humans and non-humans alike) are all connected.[4] Taking the inspiration from a spider, a creature known for spinning webs of connection, becomes an inspiration for us to consider the many points of connection we have with one another. She also refers to these connections as points in a network, and further stating: “Myriad tentacles will be needed to tell the story of the Chthulucene.” I feel like this is something that your work as an organiser and as a storyteller does, giving notice to the many and multiple ways that we are connected to one another in resistance.

I think of Donna Haraway also because of the way she uses nature as a point of reference to imagine other ways of connection. Perhaps this can be paralleled to what you say about radical imagination– confronting what feels possible, or humanly possible, to imagine another way. Albeit for her this is largely inspired by the more-than-human world. In both cases, I believe, for imagination and resistance to take place, we need to think beyond the self. We need to think and act together.

W: Yes, in interpreting diana’s visualisation I also turned to Donna Haraway. In that text you are referring to, about tentacular thinking, she argues that we must revolt, that we need action and thinking that does not fit the dominant capitalist culture. She also wonders how we should revolt and looks to on the ground collectives for their capabilities to invent “new practices of imagination, resistance, revolt, repair, and mourning, and of living and dying well”. That’s for sure what I’m hoping to do in my work, sharing stories and practices that explore those practices. For me that’s not necessarily about inventing new practice. I think there’s a lot of strong existing practice with prefigurative potential that is already happening, but also in history that we can learn from when rehearsed and improved.

M: Your background with collective movements is really apparent, from your research with the Occupy movement to your work of harvesting with Casco and within your writing, and I am interested in the ways you navigate story-telling within your own practice. I know that cooking and eating together is a big love language for you, perhaps you might also see it as a way of practising storytelling, but I’m interested to know more about the mediums you use to explore stories.

W: Cooking and eating together is definitely my big love language. I was raised with cooking and eating together and I’ve always been known to my friends as the one that enjoys cooking for everyone. Of course food tells stories, the ingredients do, the recipes, always. I’ve always made a point of that at any event that I am closely involved with organising, the food will be good and the people that are cooking and serving will be taken care of well. It’s a feminist issue for me too, to take pride in the invisible and undervalued labour. It will be noticed when it’s not there. Food always makes everything better, a way to take care of people, to bring comfort and make someone feel welcome.

My place in the art world revolved around the kitchen and cooking for a few years. Within art, I came to food from a perspective of commoning or collectivising space, more specifically, the kitchen. Together with Jun Saturay, Grace Lostia and Alejandro Navarro, we set up the Basic Activist Kitchen for Jeanne van Heeswijk’s Trainings for the Not Yet.[5] When Jeanne invited me, she gave me options to choose what I wanted to do. She suggested I could help annotate or map our different things, or discuss the squatting community in Utrecht, or she mentioned they have the unused kitchen that’s going to be activated. And quickly I knew, yeah, I’ll go there. It was an experiment proposing to turn the unused kitchen into a “venue/platform where the appetite for revolutionary change is stimulated and where conversations are about taking collective action to quench the hunger for freedom and satisfy the thirst for justice”, as our manifesto stated.

When the Trainings ended, I moved on to develop a Casco-led course at the Dutch Art Institute on the topic of food commons and ecologies of belonging together with the wonderful artist Müge Yilmaz.[6] Through food, while cooking, you deal with other things, with hierarchies in the kitchen, with the destruction that monoculture brings or the healing magic of permaculture. That year in general was totally a healing journey for me, to be offered the privilege to study more deeply together with the lovely students in our course, some of whom became good friends.

M: There really are a lot of ways to open up the politics around food, from within the kitchen to what ends up on our plate. I, personally, have been dealing with this with my own research around strawberry production. What happens when the information around production is revealed, especially when the production can often be extractive or exploitative? When you have these conversations about, for example, worker exploitation or soil degradation from overuse, be it in strawberries or palm oil, does it change the taste? Does it change the way we consume it?

What do you think is ideal for how one should be receiving this information? Or, rather, what do you think that this information can do for people? Because I don’t want people to be saying “never again am I going to eat a strawberry.” That’s not really the point. These exploitations will still happen, even if you just decided that you don’t want to eat a strawberry. I think you can look at most things and question maybe we should be doing it differently, and does talking about it while eating change those things?

W: Well, it can change consciousness and perspective. Maybe it doesn’t change the structural problem itself. But if people don’t know, then that’s even harder. I think talking about it it’s not enough, but it’s a start.

M: Perhaps for you, in being together with the preparations and with this kind of knowledge transfer through talking about food and its origins, you are also addressing how we position ourselves as consumers. All of a sudden you’re confronted with the structures that we’re entangled in, be it sexism, racism, classism, etc. There’s different kinds of structures of exploitation that are made more apparent when you really start to question where some of these ingredients come from?

W: Something that has always been important for me is that once you have the systemic critique, I want to know what is the alternative. Capitalism is a problem, but what is a non-capitalist way of doing economy or living together? The Zapatistas and the occupy movement told us that another world is possible. It’s possible, but we don’t really know how to do it yet. That’s why the commons is interesting to me because it is talking about a utopian horizon as something to work towards, but also as something already happening.

M: It’s proposing a structure to be inhabited. With commoning, it’s also an acknowledgement that the structure needs to change and develop. It’s not foolproof, right?

W: Not at all! There are also commercial and capitalist commons. That’s why Silvia Federici is important here because she talks about the anti-capitalist commons.[7] You can have a cooperative community, it can be exclusive and racist, but it can still be a commons. It can still be a community like taking care of their beautiful house all together, but it doesn’t resolve the systemic problem. We should be critical. Whom does it serve? What is that community?

The commons can offer a real alternative: they offer a real way to do things differently. That’s what I’m interested in. I, of course, believe in big revolutions, big, worldwide shifts in consciousness and doing, like the resistance against the genocide in Gaza, but, even more, I strongly believe in the revolution of daily life. How can one influence their direct environment within their community, within their friends, within their family? What can you change that is societally or systematically oppressive? What can I change in my life and in my direct environment?

So you can think, “the food system is so messed up” and “my gosh, the supermarkets waste so much food,” but realize there are people already doing something to resist it. Work with them to see what they do and learn from that.

However, I don’t really consider myself having chosen food practice as an art practitioner. It just happened. It was an institutional demand. It was a collective signifier that could connect everything, all the communities I was working with. It was a way where I could bring everything together that made a lot of sense. But, um, I’m not working on food right now…

M: Ah- right! You’re working in theatre these days! You’ve been active in Theater Utrecht! I think working in theatre makes a lot of sense for your practice, because already you have this affinity towards storytelling, but also working with other people. Theatre can bring those two things together quite naturally.

W: How I’ve been looking at my work and my practice in the past 10 years is that I have generally been fulfilling a collective demand, and didn’t really develop a clear individual practice. Although, if you look at my work in the past 10 years, there is a trajectory, it’s all action-research, organising and facilitating collective practice. I think they call it social practice now. However, I noticed that after so much collective work, I also kind of lost myself.

I lost understanding what it is that I do, or what I contribute, somewhere in between curatorial, artistic and cultural. When it comes to art forms, I really love theatre. It’s a form that really moves me. For example, sometimes you have an academic text that takes you four hours to read, and then you need to read it again because you don’t understand it, and maybe still then you don’t understand it. But in theatre, you have a person that does a monologue, saying very similar things to these academic texts, and they just talk at you for five minutes and you just start to cry. It can move you in a different way.

For myself, the most exciting collective work that I’ve done was a theatre piece.

M: When you say exciting, is that because it clicked and made sense, and you could see how bringing all these different elements together could work for you? Did this medium help you to host the ideas you were hoping to share?

W: What’s always been one of my stronger mediums is writing. It’s been in everything I had to do. I had to deliver clear writing for communication purposes. But when writing for myself, it moved much more towards the poetic or the rhythmic.

With the activist kitchen we started working on a theatre piece. I was so inspired by the people I was working with, especially Jun Saturay, who became somewhat like a mentor to me when finding a creative place for myself within activism. I would look at people singing in a choir or doing all these cool and creative things thinking to myself, “I want to do that too, but instead I’m here organising volunteers, planning the march route and getting the program together”. I wanted to find my own creative voice.

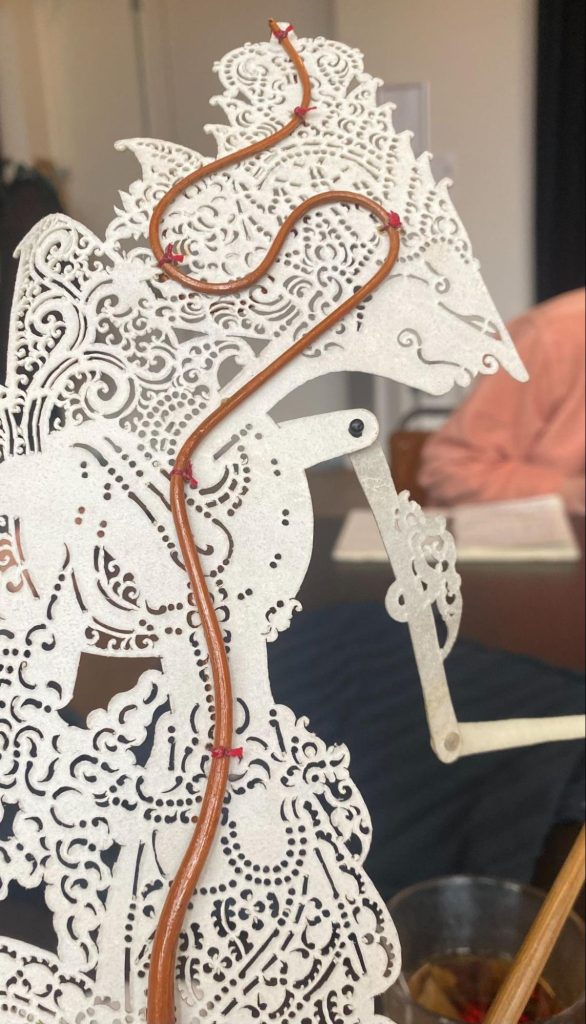

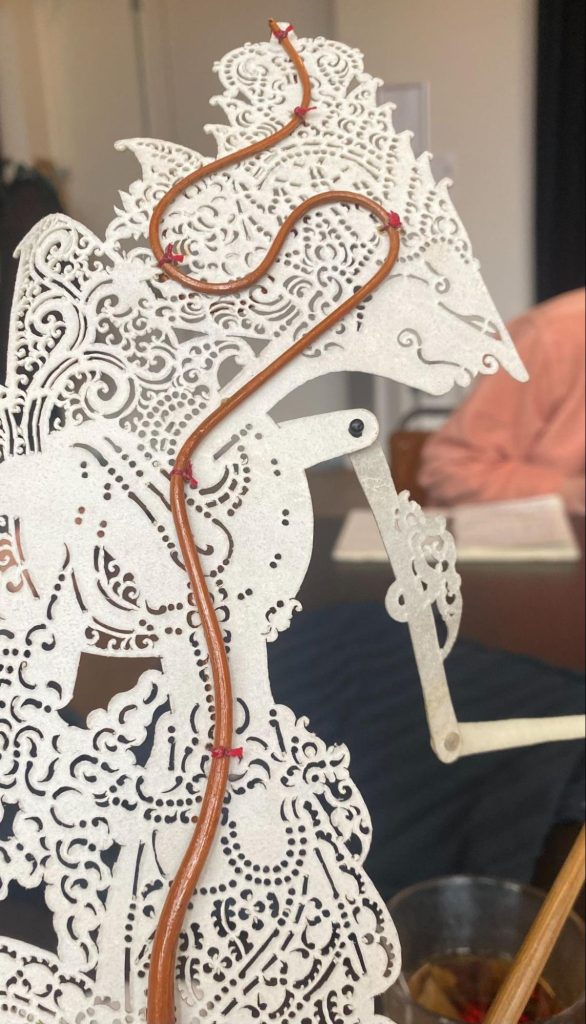

Jun showed me the impact of theatre in the street. Theatre often has this impression that it’s hosted in big places and is for the elite, but street theatre can be for anyone. I really loved that. When we worked on a performance for International Migrant Day, I don’t know, it just flowed. I just loved the whole process; envisioning the concept, writing the text, building the props. We made huge puppets out of cardboard, bamboo sticks and tulle and performed a mourning procession. A spirit family of perished migrants haunted the streets that evening, reminding people of those who lost their lives trying to cross borders or waiting to receive asylum. Our group stayed together and did something for every Migrant Day for a few years after that.

We had dreams of Shadow Play, but we grew apart. Still, whenever I see Jun, we talk about it.

M: Are you working towards a specific production at the moment? Do you already have an idea of a play in mind?

W: Yes, I’ve been working on the development of a play. I’ve been doing research since 2017, around the Indonesian women’s movement, the new order regime from Suharto and the 1965 massacres. It’s a lot of historical research and the material is very heavy. I keep trying to find ways to process it. I have tried in radio form for example, together with Elaine W. Ho for our research in BAK’s Ultra Dependant Public School, but I still didn’t manage in a satisfactory way.

M: How are you approaching this story building? Are you working from a central figure? Or are you kind of working from a period in time?

W: At the moment, the story is not there yet. I’m still world building. I know it will be a fairy tale, something aspiring to be folklore. I know it’s around hope and resistance in which historical elements are the ingredients. The material I have is very violent, about torture and massacre, about the history of slavery, the destruction of the communist movement, about oppression. I mean… It’s a lot. I’ve been grappling with that for the past seven years. And I’ve been looking for a way to tell these stories without reproducing the violence so directly. Looking for how to reclaim the history, but still, draw the lessons from it. Because it’s also a piece of history that is forgotten and silenced, so it needs to come out. We need it for the next generation, to remember… to really remember what happened. Like, “why do you think the left is as weak as it is? Why is it like that?” There’s an explanation. It’s historical. But, how can we tell that story? I think fiction is one way. It became so heavy that I had to let it go for a year.

But then I got this residency offered at Theatre Utrecht. They offered to help me develop something. So I thought, okay, this is cosmic. I’ve been wanting to do theatre, this is the moment. I should do it now and find a way to take all these ingredients from history and transform it into something that can be hopeful and inspiring. Something that we need now.

M: Totally. What you say about history being silenced and erased, it’s making me think a lot about Naomi Klein’s book, Doppelganger.[8] The book itself is a critical analysis of how conspiracy theories spurred from the Right often mimic or reflect the ideas of the Left. In it, she writes about the Jewish relationship with Israel, in a really critical and amazing way, and says that often the Holocaust remembered in numbers, and the utter horrors of violence. At Auschwitz, you have to see all the piles of shoes. It’s about remembering the pain and trauma. Because we cannot let anything like this happen again. But it doesn’t ask where to go from here. Rather than learning from the past, it instead re-traumatizes through the stories. Is there a way that we can learn from this? When most of what is taught is focused on the pain and the suffering, where are the stories of resistance? Shouldn’t these be the stories we share?

W: Yeah, exactly that. That’s a huge challenge. For me it’s been twofold, because there’s been these two periods, right? So there’s the history of slavery and the calls for critical fabulation by Saidiya Hartman and many others. The Dutch zeitgeist right now is also that people have been discussing more the history of slavery, especially through Gloria Wekker’s book White Innocence, the collective demand in the Netherlands is to acknowledge these histories. The king, the prime minister, the mayors, they’ve been apologizing for the role the Netherlands has played in the global slavetrade that has made this country so wealthy. So that’s one part. But then going to Indonesia, and looking through my own roots, family and identity, I learned about what had been happening to the Chinese in both the Dutch Indies and after in Indonesia. I learned why my family ended up leaving in the 50s. I also found that in Indonesia, people are not so busy with the history of slavery. They are busy dealing with a later trauma, namely, what has happened during the New Order regime. This period from 1965 to 1998 is called the undocumented period. Any dissonant voice, everyone who posed a threat to the regime was locked up, killed, silenced, or exiled. It’s still not really safe to talk about what actually happened

So I found myself split between these two periods, the history of slavery and the New Order regime. It’s filled with trauma and pain. We need to remember that, but we also need to reclaim those stories. So that it’s not just the pain and the trauma. Because aside from that… There is also always joy. There is always love, and there is always resistance. We have to remember, especially since we’re in really dark times now. For a while already, you know? With Gaza and the new government…It’s gonna be really difficult.

Maybe it’s more important now than ever to have these stories of how people survive these things. Not just survive, but also how can you grow or change a society or a community after something like this happens? And how to fight, and give some hope.

For me to process what I learned, I think I just need to make it like a magical folklore story.

M: Yes, I think everyone needs it, now more than ever.

photos provided by Wan Ing Que

[1] Militant Ethnography is a model of politically engaged participant observation. “Such an approach is meant to challenge the divide between researcher and activist, using [a] dual position as an organizer and anthropologist to not only gain access to movement networks, but also to generate deeper knowledge and more innovative theoretical insights about movement practices, experiences, emotions, and internal political struggles and debates than would otherwise be possible.” Militant Ethnography, Jeffrey S Juris. Accessed online, 2024.

[2] In Spanish, compa is short for compadre or companera, translating to a good friend, companion, or a comrade.

[3] Lola Olufemi, Experiments in Imagining Otherwise (Maidstone: Hajar Press, 2021).

[4] Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Experimental Futures Technological Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices (Durham London: Duke University Press, 2016).

[5] Exhibition at BAK (Basis voor Actuele Kunst, Utrecht) held from September 2019 – January 2020

[6] The class was a part of DAI’s COOP study trajectory, titled You fed me when I was hungry. Held from September 2021 – August 2022.

[7] Silvia Federici, Re-Enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons, Kairos (Oakland, CA: PM, 2019).

[8] Naomi Klein, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World (London, UK: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books, 2023).